America’S Housing Paradox, Hiding In Plain Sight | Money With Katie Blog

In June, Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies released a report that confirmed the obvious but unbearable reality that most aspiring homeowners recognized long ago: The median income cannot afford the median life. To meet traditional lending criteria for the middle-of-the-road home today, a prospective buyer would need to reliably pull down at least $126,700, an income that only 6 million of the nation’s 46 million renters claimed as of 2023. Maybe it’s a moot point—renting a starter home is an average of $908 per month cheaper than buying one in 49 of the 50 largest markets. Despite those savings, half of all renters are “cost-burdened,” spending more than 30% of their income on housing, with a quarter spending more than 50%, leaving virtually nothing for DoorDashing avocado lattes.

This state of affairs has created the rare bipartisan consensus that the US is tangled up in an unprecedentedly knotty housing crisis. It’s a situation that everyone from the libertarian Cato Institute to center-left pundits present as a classic supply-demand mismatch. Depending on your calculation method of choice, the US is allegedly short by anywhere from 1.5 million to 5.5 million housing units.

In housing parlance, a “shortage” can refer to either units themselves—for example, there are 10 families in this neighborhood and only seven houses—or it can refer to the inability of existing inventory to meet demand affordably. Maybe there are 10 families and 12 houses, but six of those houses have cold plunges and heated driveways and therefore cost more than most of those families can afford. Right now, the popular understanding of our national housing predicament applies the former interpretation. The data suggests the latter.

“Right now, the popular understanding of our national housing predicament applies the former interpretation. The data suggests the latter.”

A 2024 University of Kansas study found that between 2000 and 2020, housing production outpaced household growth by 3.3 million units. When I called Kirk McClure, one of the paper’s coauthors who’s been studying housing since the 1970s, he told me he had been skeptical of the prevailing narrative that there were too few homes, but “was convinced [he] must be wrong.” Originally, he and his research partner, Alex Schwartz, set out to map the shortage so they could study its causes. But a shortage wasn’t what they found. Of the 907 metropolitan and “micropolitan” areas they studied, only 23 demonstrated a lack of sufficient units. (McClure described rolling out these findings, which ran uncomfortably counter to the leading understanding of the problem, as “an uphill slog.”)

The real crux of the problem, McClure and Schwartz wrote, is “the mismatch between the distribution of incomes and the distribution of housing prices.” A tidbit in the Harvard Joint Center for Housing report seems to validate their view: In 2024, development of multifamily housing hit a four-decade high of 608,000 new units—but “much of the construction was at the upper end of the market.”

Sufficient inventory or not, something clearly isn’t working. And because every market features an array of unique variables, it’s difficult to isolate cause and effect when comparing outcomes. The relatively lawless Houston, Texas, for instance, famously has no formal zoning laws, but it also boasts an expanse of more than 600 square miles with which to house its 2.4 million residents—more than 26 times as much land as Manhattan’s paltry 23 square miles for 1.6 million people. Because Manhattan houses 20x more people per square mile, contrasting the two cities’ housing results as a function of, say, their approaches to zoning is basically useless. Local labor markets, climate, and land itself are all stars in a constellation of factors that influences prices in any given zip code.

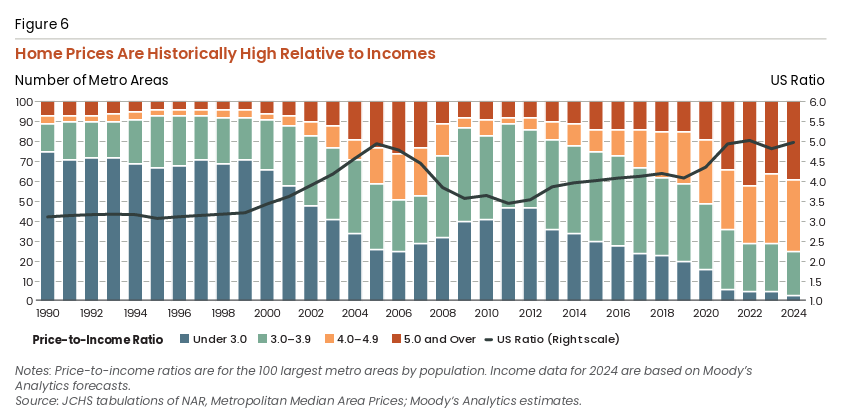

But one thing is certain: The crisis is national. In 1990, the median home cost less than 3x the median income in more than 70% of the largest metro areas. Today, there’s virtually nowhere that’s true.

Joint Center for Housing Studies.

There are a few leading theories for how we got here: First, there’s the narrative of chronic under-building that followed the financial mushroom cloud the American banking sector detonated over the world economy in 2008 (exacerbated by, apparently, a glut of unnecessary local ordinances and environmental regulations). Then, there’s the private equity firms and investment banks or, their shorthand, Blackstone. Finally, you’ve got the large millennial generation coming of age and trying to buy homes simultaneously. All of these stories are compelling, and all are, at least, half-true—but regardless of the explanation du jour, they all tend to aim the laser pointer at the same broad solution: compel the market to provide more houses. I’m a proponent of more building, but a narrow focus on constrained supply alone mistakes a symptom for the disease itself, leaving the underlying power dynamics and incentive structures unexamined.

For one thing, McClure finds the fashionable perspective that zoning reform will increase supply dubious. He said it tends to move housing development around, rather than spawn more of it. “We will simply cause those rentals that would have been built in a largely multifamily area…to be dispersed more broadly across the markets, and some will find their ways into areas formerly zoned for single-family housing.” The housing industry is, he said, “a pretty well-oiled machine,” making development decisions based on vacancy rates. In other words, zoning has less influence on how much housing is built, and more on where housing is built.

“There are benefits to be gained from [zoning reform],” he said, “but we’re not going to see a price effect, because we’re not going to build any more units.” While I’m hesitant to draw sweeping conclusions from Prince’s hometown, Minneapolis experimented with eliminating single-family zoning in 2019 and the results were modest—a net gain of 255 housing units in the following 2.5 years for a population of around 430,000 people. A 2023 Urban Institute study of 1,136 cities found that loosening restrictions was associated with a 0.8% increase in housing supply within three to nine years, and predominantly “for the units at the higher end of the rent price distribution.” (“We find no statistically significant evidence that additional lower-cost units became available or became less expensive in the years following reforms,” the authors wrote.) It’s easy to miss what the zoning debate takes for granted: that more inventory of any kind is the straightforward solution, and all that’s left to do is thumb-wrestle about the best way to make the market provide it.

“Housing is the only commodity that is both necessary to sustain life and, simultaneously, a speculative asset expected to make its owner rich.”

Housing occupies a unique lane in our economy. It’s the only commodity that is both necessary to sustain life and, simultaneously, a speculative asset expected to make its owner rich. In the US, it also happens to be unusually illustrative of the way our cultural norms impact our ability to assess solutions clearly. The existing emphasis on increasing supply conceals a critical paradox. Jerusalem Demsas summarized it perfectly:

At the core of American housing policy is a secret hiding in plain sight: Homeownership works for some because it cannot work for all. If we want to make housing affordable for everyone, then it needs to be cheap and widely available. And if we want that housing to act as a wealth-building vehicle, home values have to increase significantly over time. How do we ensure that housing is both appreciating in value for homeowners but cheap enough for all would-be homeowners to buy in? We can’t.

As long as policymakers, buoyed by a homeownership-obsessed electorate who vote accordingly, are unwilling to confront this fundamental tension, we’ll be limited to affordability solutions that must teeter along an impossible tightrope.

The supply-side critique—which chiefly targets development obstructionists like municipal governments staffed by climate-obsessed liberal scolds and “NIMBYs,” or existing homeowners who don’t want their property values to decline—argues that removing such obstacles will unleash a wave of building, thereby solving our affordability crisis. But setting aside any evidence to the contrary and assuming that the evaporation of city codes and rich ex-hippies’ grievances would have the intended effect, play that scenario out: The moment it begins working too well—when enough homes are built to achieve the purported goal of a meaningful slide in prices—you’re faced with the opposite crisis, a swath of middle-class homeowners whose primary source of wealth is losing value every year. (This will be especially relevant for those who almost certainly overpaid after 2021 and would be treading upstream for years if they ended up underwater on their mortgages.)

Rich San Franciscans with “IN THIS HOUSE WE BELIEVE” yard signs are the typical NIMBY avatar—rarely a sympathetic group for either political party. But this is hardly representative of the average American homeowner. Homeowners as a class are significantly wealthier than renters (as the National Association of Realtors loves to remind us), but it’s unfair to depict the group as a monolith that’s perennially squatted in the empty lot next door, elbows splayed from a defensive crouch, boxing out construction for a few extra points of appreciation. Nearly a quarter of all homeowners are cost-burdened like the renters, spending more than 30% of their income on their mortgage, taxes, and insurance. Because of the very incentives Demsas describes, US culture and policymaking alike have, for decades, marshaled generations of people—most of whom are not Bay Area-based B2B software company founders—onto a one-way street where each mortgage payment supposedly represented another paver on the yellow brick road to guaranteed long-term stability in an unstable system. When home equity is excluded, the median net worth in the US is more than halved.

Ignoring the conflicts of interest that decades of US policymaking have created makes pushing for more supply (let alone the right type of supply) an eternally Sisyphean task; a boulder we’re doomed to shoulder up the mountainside forever while quibbling over sidewalk ordinances and praying we can strike the exact right balance to avoid tipping either group into peril.

It’s a Catch-22: If you produce only a moderate amount, prices don’t soften enough to make housing meaningfully more affordable for prospective buyers, and those who already own capital are more likely to see (and act on) an investment opportunity. If you somehow manage to convince private-market developers to create “extreme supply”—enough to dwarf demand and substantially impact affordability—you risk trapping existing owners in mortgages that are now larger than the values of their homes in a country where most working people’s largest asset is—you guessed it—their home.

“Ignoring the conflicts of interest that decades of US policymaking have created makes pushing for more supply (let alone the right type of supply) an eternally Sisyphean task.”

So if there isn’t a true “shortage,” why are houses so expensive right now? Since just 2019, home values have jumped by 60%. To put this into terms your average Zillow aficionado can immediately appreciate, a home that cost $200,000 six years ago would now list for $320,000. The sharpest increase—a 38% jump from a median sale price of $317,100 in Q2 2020 to $437,700 just two years later—maps closely with the pandemic-era quantitative easing. At the risk of violating the Yoda-like rule of armchair analysis that “causation does not correlation equal,” during the same period, the M2 money supply surged by about 38% as well, from around $16 trillion to $22 trillion.

The relationship between monetary policy and asset prices is more complex than this coincidence might suggest, but to ignore its role outright in favor of overweighting alternate explanations—like the explosion of post-pandemic millennial household formation—seems like sidestepping the elephant in the formal living room. After all, the rate of household formation has been slowing for decades—growth in the period between 2010–2020 was the lowest ever recorded.

Joint Center for Housing Studies.

Even a bunch of late bloomers synchronously exiting their parents’ basements stage left carries less plausible explanatory power than the reality that a flood of new money pooled in assets and pushed the prices of everything from stocks to two-bedroom condos to unprecedented high-water marks. This will always be the unavoidable, if unfortunate, consequence of treating housing as an investment, stranding us to frantically search for other levers—like indirect, trickle-down manipulation of supply—to offset the fundamental truth of our incompatible goals. Lofty stock price growth that’s disconnected from any real increase in value is a problem, too, but with one key difference: We don’t host our dinner parties inside index funds. When stocks are overpriced and every dollar buys fewer shares, we can simply buy less until values rightsize—but you don’t stop needing somewhere to live just because rents rose by 20%.

“When stocks are overpriced and every dollar buys fewer shares, we can simply buy less until values rightsize—but you don’t stop needing somewhere to live just because rents rose by 20%.”

Because of the inherent tension in America’s housing incentive structure, maintaining this precarious balance will continue to require ongoing careful intervention. You may remember Vice President Harris’s campaign proposal of a new $40 billion tax credit for developers who build homes for first-time homebuyers. TThis subsidy, borrowing the logic of a public-private partnership, was intended to “facilitate” the construction of a stunning 3 million houses; the implication being, of course, that developers are currently insufficiently incentivized to build the type of housing we need.

But developers, landlords, and real estate investors are already disproportionate beneficiaries of the US tax code—from the ability to deduct depreciation to the famed 1031 exchange, the perks of profiting from housing are plentiful. Even renter-focused benefits like housing vouchers end up accruing to owners: The $46 billion in emergency rental assistance funds of 2021 had the practical effect of a capital subsidy, with tenants acting as a mere pass-through entity for checks which first visited landlords on the journey to their final destination, the banks the landlords were paying. Hopefully it goes without saying: Preventing people from being evicted is necessary in any society that claims with a straight face to have a conscience. The issue is not that tenants were supported, but that in our current paradigm, “tenant support” essentially amounts to welfare for capital, which has the self-defeating net effect of making housing even more attractive to people who want to make money from it instead of live in it.

Government intervention is an indispensable fixture of an arrangement in which something every human needs must also double as a speculative piggy bank. The visible hand which intermittently juices or softens demand uses four of its five fingers in service of underwriting the “line go up” philosophy of American home values, so it’s tempting to look at this state of affairs and deduce that government intervention writ large is the problem. The better question is not about “how much” government we want, but which goal and whose interests do we want that government to serve, and how directly?

“The better question is not about ‘how much’ government we want, but which goal and whose interests do we want that government to serve, and how directly?”

Historically, housing in the US has been the primary way regular people could build equity as a byproduct of living their lives. Rather than designing a system in which shelter was treated as a public good and the path to building equity was instead linked to, say, productive labor—in which work would directly generate ownership in the economy over time—we tied equity for the masses to the ownership of unproductive land and the deteriorating structures we build on it.

At this point, the reality that the median home costs something like “five times median income” is as much a commentary on income as it is on homes. Or, as McClure told me: “We have too many people whose incomes do not permit them to enter the market, even though the units are there.” Understanding the dynamics that are creating the outcomes we don’t want is necessary for resolving them, because right now, “The belief that we have a shortage is causing people to change policies, and not for the better.” Looking for solutions to affordable housing without addressing or even acknowledging underlying trends like class dynamics, income disparity, and the conflicting simultaneous goals of US housing policy means we will never cure this disease, only continue to poorly manage it.